Last year, in an interview with the New York Times, anthropologist Heidi Larson, founder of the Vaccine Confidence Project, said that efforts to silence people who doubt the efficacy of the Covid-19 vaccines won’t get us very far.

“If you shut down Facebook tomorrow,” she said, “it’s not going to make this go away. It’ll just move.” Public health solutions, then, would have to come from a different approach. “We don’t have a misinformation problem,” Larson said. “We have a trust problem.”

This point rings true to us. That’s why, as we face growing pressure to censor content published on Substack that to some seems dubious or objectionable, our answer remains the same: we make decisions based on principles not PR, we will defend free expression, and we will stick to our hands-off approach to content moderation. While we have content guidelines that allow us to protect the platform at the extremes, we will always view censorship as a last resort, because we believe open discourse is better for writers and better for society.

This position has some uncomfortable consequences. It means we allow writers to publish what they want and readers to decide for themselves what to read, even when that content is wrong or offensive, and even when it means putting up with the presence of writers with whom we strongly disagree. But we believe this approach is a necessary precondition for building trust in the information ecosystem as a whole. The more that powerful institutions attempt to control what can and cannot be said in public, the more people there will be who are ready to create alternative narratives about what’s “true,” spurred by a belief that there’s a conspiracy to suppress important information. When you look at the data, it is clear that these effects are already in full force in society.

We are living through an epidemic of mistrust, particularly here in the United States. Trust in social media and traditional media is at an all-time low. Trust in the U.S. federal government to handle problems is at a near-record low. Trust in the U.S.’s major institutions is within 2 percentage points of the all-time low. The consequences are profound.

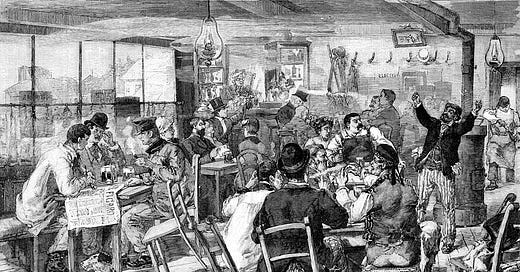

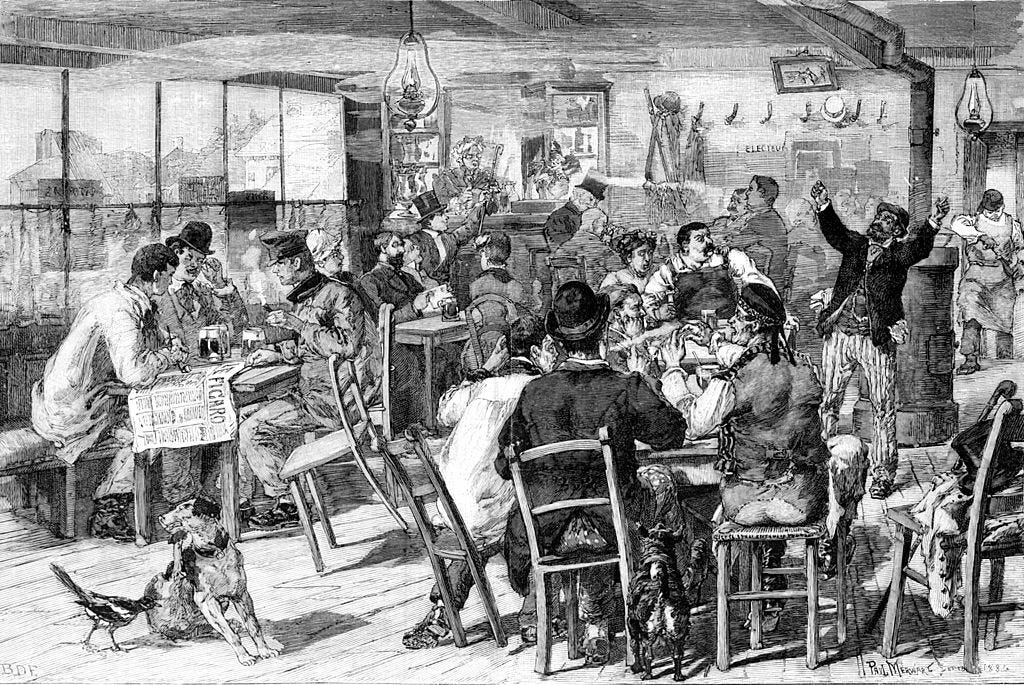

Declining trust is both a cause and an effect of polarization, reflecting and giving rise to conditions that further compromise our confidence in each other and in institutions. These effects are especially apparent in our digital gathering places. To remain in favor with your in-group, you must defend your side, even if that means being selectively honest or hyperbolic, and even if it means favoring conspiratorial narratives over the pursuit of truth. In the online Thunderdome, it is imperative that you are not seen to engage with ideas from the wrong group; on the contrary, you are expected to marshall whatever power is at your disposal – be it cultural, political, or technological – to silence their arguments.

In a pernicious cycle, these dynamics in turn give each group license to point to the excesses of the other as further justification for mistrust and misbehavior. It’s always the other side who is deranged and dishonest and dangerous. It’s the other side who shuts down criticism because they know they can’t win the argument. It’s they who have no concern for the truth. Them, them, them; not us, us, us. Through this pattern, each group becomes ever more incensed by the misdeeds of the other and blind to their own. The center does not hold.

Our information systems didn’t create these problems but they do accelerate them. In particular, social media platforms that amplify contentious content contribute to the intensification and spread of mistrust. At the same time, they ratchet up the pressure on traditional media – legacy print, TV news, radio – to vie for attention at all costs, with similar consequences. People start to fixate on branding their opponents as peddlers of dangerous misinformation, threats to democracy, terrorists, and charlatans. In a frenzy to kill all the monsters, we keep creating more monsters – and then feeding them. All the while, the range of acceptable viewpoints and voices within each group gets ever narrower.

This is the area where we hope to make a contribution with Substack. While the attention economy generates power from exploiting base impulses and moments of attention, a healthy information economy would derive power from the strength and quality of relationships that are built over time. The strength of these relationships would depend on the writers and readers not feeling like they’re being cheated, coddled, or condescended to. Knowing that they are on a platform that defends freedom of expression can give writers and readers greater confidence that their information sources are not being manipulated in some shadowy way. To put it plainly: censorship of bad ideas makes people less likely, not more likely, to trust good ideas.

The key to making this all work is giving power to writers and readers. That’s why at Substack we focus on subscriptions instead of advertising, and it’s why Substack writers own and control their relationships with their readers. To paraphrase someone who ought to know, these people do not look to be ruled. Our promise to writers is that we don’t tell them what to do and we set an extremely high bar for intervening in the relationships they maintain with their readers.

Not everyone thinks this is the right approach. Many people call for greater intervention, as has become increasingly common on other platforms, making companies the arbiters of what is true and who can speak. To those who endorse such an approach, we can only ask: How is it going? Is it working yet?

We will continue to take a strong stance in defense of free speech because we believe the alternatives are so much worse. We believe that when you use censorship to silence certain voices or push them to another place, you don’t make the misinformation problem disappear but you do make the mistrust problem worse.

Trust is built over time. It can be rebuilt over time, as long as those in positions of responsibility don’t succumb to pressure to take shortcuts. Trust can’t be won with a press release or a social media ban; and it can’t be strengthened by turning away from hard conversations. It comes from building and respecting relationships. For the media ecosystem, it requires building from a new foundation.

That is the work we commit ourselves to at Substack. It is hard, and it is messy. It is the only way forward.

Share this post